[ad#250]

Keeping reptiles as a hobby began out of a necessity and developed into a passion. I’ve always had an interest in animals, but it wasn’t until my sophomore year in college that I actually started to keep reptiles. At the time, I was studying to become a mechanical engineer and I needed an outlet to relieve stress. So after spending several months on an online forum, I picked up my first leopard gecko (Eublepharis macularius) from a local store. Months later, I found myself with another leopard gecko and started to look into geckos of the Rhacodactylus genus. The more I read about these animals in my spare time, the more interested I became in keeping different ones.

Getting Started

Fortunately for me, a few “seasoned” breeders took me under their wings soon after entering the hobby. We’ve all heard horror stories about poor care guides and suffering animals, but I was determined to start on the right track. I searched out the breeders that had been around for more than a few minutes and who seemed to have success at breeding a variety of animals. (I’ve exchanged many thousands of emails over the years and spent hundreds of hours on the phone simply garnering husbandry advice.) As I began to meet new people, the opportunity to acquire “less-kept” species began to be more frequent. Many of those opportunities were missed, but I did take advantage of a few. With the aid of other breeders, my collection began to increase steadily over the years and I’ve made my share of good friends as well. That increase has manifested itself into a modest collection of mostly geckos from around the world.

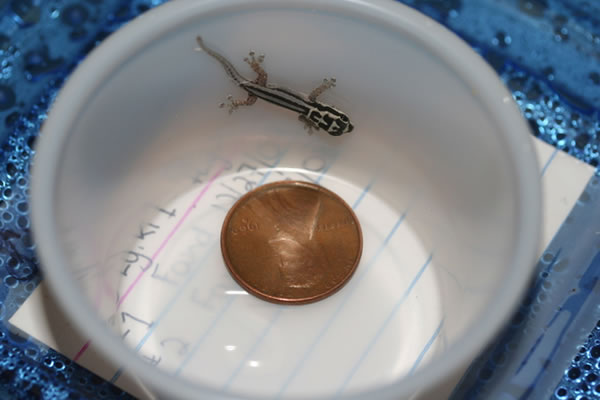

One of my first challenging species was Phelsuma lineata bombetokensis, a diurnal (or “day”) gecko species from Madagascar. This small day gecko is a beautiful shade of green with red spots and should be a poster-boy for Phelsuma! Fascinating and active, they not only fostered an interest in other geckos of that genus, but diurnal geckos in general. Today, about half our gecko collection is filled with day-active species. While a number of the species we work with are classified in the same genus, their care can be as different as night and day. Managing animals with various care requirements can become a real chore if you can’t find a balance in your husbandry. Over the years I have developed (and still fine-tuning) a methodology that attempts to keep maintaining a collection fun and rewarding. Some might insist that has to be challenging given the diversity present in our collection. Currently, we work with over 70 species representing nearly 30 genera, some of which include Anolis, Homopholis, Lygodactylus, Pachydactylus, and Quedenfeldtia. I tend to think keeping up with the Latin might be more challenging then actually looking after most of the animals.

Questions to Consider

Maintaining a large number of different species requires keen observation and an eye for consistency in husbandry. Typically keepers gravitate towards a certain “type” of animal and end up with a collection of similar species. On the other hand, there are those with eclectic tastes who manage diverse collections. Whichever route you take, there are two things to think about when you consider adding a new species, especially if you already have an established number of captives:

Is this a species where other keepers have already had success?

If so, try contacting those with “hands-on” experience. There is no need to reinvent the wheel of husbandry if unnecessary. Being aware of specific difficulties can spare you time, frustration, and the lives of animals. If it appears as if other keepers have not been successful, can you devote the time to be a “pioneer” with this species?

How is their care relative to what you already keep?

Will adding them strain your resources (time, space, electricity usage, etc.)? Can you “afford” to keep them successfully? If you can answer these questions affirmatively and assuming there are no legal complications (state permits, CITES permits, etc.) with acquiring specimens, you might be on your way to a diverse collection.

Meeting Diverse Needs

The basic building block for successfully keeping any species is to know how to satisfy their basic needs and then design their cage around those needs. A terrarium or vivarium should be designed around function first, and form or aesthetic second. There is little point in constructing a beautiful cage that fails to meet the needs of the animals and they suffer as a result. Does the animal need plenty of visual barriers to feel secure? What are their temperature and humidity preferences? How adept are they at escaping? These are the types of questions that need to be addressed when considering their cage setups. Many animals can be kept successfully in rather simple cages. As long as their needs are being met, design modifications (addition of live plants, hardscape, etc.) can be made without issue.

Once you have a suitable cage designed, you’ll need to consider the best-fit spot to place it. If you only have a few terrariums, finding a place might not be too difficult. At the same time, those with numerous racks full of cages might take some time to determine the most efficient and practical place for it to go. Here at CC Herps, we almost always place diurnal animals in aisles with other diurnal animals (after quarantine of course). With several hundred feet of rack space in use, it just makes sense for us to group animals not only according to activity, but also temperature and humidity requirements. Doing so allows us to take advantage of the natural temperature gradients present. For instance, there might be a rack with 3 or 4 shelves in it, featuring dry savannah type cages. Since all the geckos housed therein require low relative humidity, the next thing we’d consider is which (if any) prefer warmer ambient temperatures. Based on that determination, those that prefer the warmest temperatures would be placed on the highest shelf level. As a result of the natural rising of heat, we’d be taking advantage of the otherwise wasted heat associated with warming the cages below. Keeping a large collection is just as much about efficiency (in all forms) as anything.

Bringing a scaled (or smooth-scaled) reptile home can be a life-altering decision. There are hundreds of species available in our hobby, so finding something you’d like to work with shouldn’t be difficult. It’s easy to find yourself with a list pages long of animals you want to acquire, but knowing your own limits (and respecting them) can help ensure a long stay in our favorite pastime. Remember, you are charged with the well being of the animals you keep…never take that lightly.

I’d like to thank a few of my mentors: Clark Tucker, Alex Hue, Gene Richardson, Jay Sommers, Dr. Alan Slack DVM, Leann Christenson, Julie Bergmann, and Jonathon Boone. You and others have helped me along the way. Thank you for all the years of friendship and counsel.

[ad#sponsor]

Really well written article!

Harold not only keeps one of the most diverse collection of geckos you will find, but also is a limitless source of information on each and every species.

What a wonderful post, Harold! Thanks so much for sharing with us.

Thanks all for your kind remarks. Wally, I wouldn’t say I was even remotely close to a “limitless source,” but I thank you for the vote of confidence. I hope this brief article has helped at least someone considering diving into more species.

Hope you can help have some questions I would like to ask …

Regards tana

I am a breeder of giant Madagascar geckos

Crested geckos….

And gold mantellas in white neon orange , orange and yellows

Hope to hear from you soon thanks again..

I’ll be happy to answer a question as soon as you ask one.