A “first” for Gecko Time: we are publishing simultaneously a fascinating article by Hervé St. Dizier about the genus Afroedura in French, as well as this English translation of the article by Aliza Arzt.

Fig. 1 (photo www.jonboone.com) a typical specimen in its natural environment

Taxonomy: Protection Status: CITES : no Classe : Reptilia IUCN classification (endangered species):

not evaluated

Order: Squamata Common name: Loveridge’s rock gecko

Sub-order: Sauria Holotype : UM 4030 (University of Michigan)

Family: Gekkonidae Distribution: Mozambique, 8 km à l’Ouest de Tete

Sub-family: Geckonidae Range : Small range of less than 100 miles

Genus: Afroedura

Other Names: Afroedura transvaalica loveridgei BROADLEY 1963: 286

Afroedura loveridgei — BAUER, GOOD & BRANCH 1997: 453

Afroedura loveridgei — BRANCH 1998 Afroedura loveridgei — RÖSSLER 2000: 57

The species was named in honor of British biologist and naturalist

Arthur Loveridge (1891-1980).

The genus Afroedura includes fifteen taxa (species and subspecies.) To date, eleven species have been identified (source: Zootaxa ) , however, with increasing access to some of the more remote habitats and with the DNA sequencing of more of the specimens, it is likely that the number of identifiable species will increase in the near future (Jon Boone, pers. comm.). The genus is characterized by a very flat body, adapted for hiding in cracks and narrow rocky crevices. These geckos are primarily nocturnal, with an average size varying between 45 and 80 mm snout-vent length (SVL ; Alexander & Marais, 2007). The tail is a repository for fat and has a series of ridges perpendicular to its axis. The genus is strictly endemic to southern Africa (some areas of the Republic of South Africa , Angola, Mozambique, Namibia … ) and the species are geographically isolated from each other. Each species occupies a restricted territory, suggesting the probability of a common ancestor with continuous distribution. These geckos occupy rocky habitats exclusively, hence the term “rupicole” ( ie. “living on rocky surfaces”). These species are all potentially endangered, due to the reduced size of their habitat and their very specific habitat needs. The IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) has not yet listed the genus as protected due to lack of data on most of the species. However, each species can be found in very high concentrations in suitable micro- sites within their range . Communal residence in rocky sites is documented for several species (Rössler 1995). Each species lives on a specific rocky substrate (calcareous schists, granulites) away from human habitation (Alexander & Marais , 2007).

Description

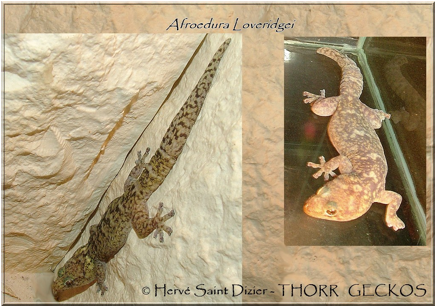

Figure 2 Adult pair showing on the left the male with a regenerated tail and on the right a female with tail intact , as well as the possible variations in coloration.

Afroedura loveridgei is a medium-sized species within the genus. It’s about 125 mm in total length , 40% of which is the tail, which has the pudgy appearance described above with 21-25 segments narrowed at their base. The latter can be detached by autotomy , though less easily than in other geckos (pers. Obs.) . The body is flattened dorso-ventrally (thickness = ≤8 mm), robust and wide, especially in the abdominal area, which is an obvious adaptation to the very particular mode of life of this species (see below). The legs are powerful, allowing for very rapid movements . The fingers have two rows of sub-digital lamellae (26 pairs of plates on the longest finger) for walking or running on very smooth surfaces such as glass. They are five toes on both the anterior and posterior legs. The skin is smooth, velvety to the touch , and uniformly covered with tiny scales. It is fragile in appearance, semi- transparent, yet resistant to abrasions in its rocky environment. The wrinkled appearance is natural and should not be considered a sign of dehydration (cf. skin of the Uromastyx flank).

The eyes are round and relatively large (ø ± 5mm), typical for nocturnal and crepuscular species, rimmed with fine, uniform periocular scales. The scales are less than 0.4 mm in adults, and entirely surround the iris. The latter is slate gray with some darker mottling, and the vertical pupil is photo-sensitive. The supra-ocular area is gray-blue to lagoon-blue. The snout is strong with rounded nostrils slightly elevated ± 4mm . The endolymphatic sacs of females are sometimes spectacularly large, suspended along the neck. This is a normal characteristic of the species and a sign of good health, serving as a reserve for metabolic calcium and used especially when breeding. The ventral coloration is uniformly white. The dorsal and lateral color of adults and juveniles is similar and varies with the intensity of the heat and light. The background color is beige-pink rosé sometimes shading more toward true rose. Tiny bright beige spots dot the back and each specimen has a different number and distribution of these spots. A marbled pattern with blurred and discontinuous contours, bluish-gray to reddish brown, adorns the back but not on the anterior, on the tail, (which is uniform and lighter in color than the body –cream with some beige rings) or on the legs. Bright yellow blotches with irregular contours complete the body coloring and serve as perfect camouflage for rocks more or less overgrown with lichens.

Habits and Ecology

The species is not entirely nocturnal, as the geckos come out to warm up especially in the morning (pers. Obs.). They frequently hunt before nightfall. Easily frightened, they hide at the slightest alarm; they are therefore not ideal for those who enjoy frequently observing their geckos in captivity. When handled, they have a surprising behavior: although they attempt to move quickly when initially handled, once on the palm or the back of the hand, they remain motionless, not trying to escape (pers. Obs.). Most of the time, they live concealed in narrow rocky crevices, safe from potential predators. They can deal with deep cracks in blocks or rock formations in the wild (up to 1.50m or 5 feet deep). Sites where they deposit their feces and urates (usually on the ground, pers. Obs.) are used communally so as not to provide specific indication to predators of their location. They occupy ecological niches in a hot and dry climate, with the typical seasonal variations of Southern Africa (mild winters, hot summers, heavy rains in season, but with an overall dry to very dry atmosphere under normal circumstances). They press themselves against the hot stones during the day to achieve thermoregulation. In their microhabitat, temperatures can rise very quickly during the day (up to 40-45 ° C , higher on the hot rocks exposed to the sun ) , hence the tendency to retreat to crevices and shady hollows once ideal body temperature has been reached through basking.

Fig.2b: Portrait of a female, showing the importance of the endolymphatic sacs (H. Saint Dizier)

Fig.2c: View from above of a healthy adult female and her endolymphatic sacs

Fig . 3: natural environment near Tete, Mozambique , Chirobue rock , basically the type of rock formation where Afroedura loveridgei lives. (Source : Wikipedia commons , royalty free )

They are strictly insectivorous and the prey they consume in the wild is small relative to their own size: small beetles, termites, grasshoppers, larvae, etc.; their mouths do not permit them to ingest larger prey (Broadley, 1964). Longevity has not been studied, however a lifespan on the order of a dozen years or more under optimum conditions seems realistic given that of other more well-known species.

Dimorphism and Sexual Maturity

Sexual maturity occurs in normal conditions around the age of one year, however fertile clutches do not occur before the end of the second year (pers. Obs.). There is no marked sexual dimorphism: the pores are absent in both sexes, the male hemipenal bulges are fairly marked but not prominent so as to avoid abrasions and injuries in their rocky environment. It is almost impossible to determine the sex of juveniles until at least nine months of age.

Maintenance in Captivity

The females are very tolerant of congregate living. Of course cohabitation of males is prohibited. A vertical glass terrarium 40x40x60 cm (16”x16”x24 ‘) is perfect for a small group of one male with one to three females. It is essential that the enclosure is well ventilated and escape-proof . For my part, I use a terrarium with a “Guillotine” opening, as opposed to sliding doors in order to minimize the risk of escape. These geckos can seem indolent and then suddenly flee with great speed. The substrate is of little importance since these geckos almost never descend to ground level; I use about 2-3 cm (1”) of children’s play-sand. This substrate is refreshed completely every six months.

Figure 4 : Terrarium Under construction without the lighting

These geckos are less stressed in an environment which is opaque on the three vertical sides of the terrarium, except of course the front. To accomplish this, and in order to best comply with the conditions of their natural life, I install three vertical sides of “facing stones” sold as wall decorations or interior fireplace liners. These are about 1 cm (1/2 “) thick, and are securely affixed with aquarium silicone (dried in a well ventilated room for one week, since fumes of dry silicone are highly toxic to reptiles) . In fig.4 we see the decoration under construction, with the facing stones running towards the top of the walls. The top of the terrarium is covered on the outside by an opaque plastic, apart from the space reserved for ventilation. A water dish on the ground will not be utilized by these geckos. Instead, I use a shallow bowl affixed with silicone at an angle in a corner and located halfway up the terrarium, near the bottom. A 16 watt heat mat is placed on the outside against the glass of the bottom in a vertical position and is connected to a thermostat . A halogen lamp (spot ExoTerra® type) serves as the main heating (simulating solar radiant heat) and daytime running lights. The power is adjusted according to the seasons, and this lamp is paired with a fluorescent tube (5% UVB Zoomed® 14 watts). The main lamp is turned off in December and January, when only the heat mat and the UVB tube remain in use; from February to mid-April and in October, the power output is 40 watts. In the summer (mid- April to mid- September) I use a 60 watt halogen spotlight. It should be noted that these spots also emit UVA . Although they are theoretically nocturnal (see below), exposure to UVA and UVB has proven to be beneficial and I was strongly advised to use it (Jon Boone, pers. Comm.). In the case of an unusually hot summer, I reduce the power of the main lamp to 40 watts.

Artificial plants can be used for decoration, as in fig.4. I had originally placed some branches in the enclosure, which were never used by the geckos. It is essential to have stones and slates or tiles with gaps between them. The stones should be cemented to the ground with the same silicone adhesive to eliminate the risk of them dislodging. I use local stone (Jurassic “Caen limestone” of a typical blond – beige color, often inlaid with fossils and easy to find in my area) as well as gray slate (dull the edges with an emery board or coarse sandpaper) placed vertically, as well as tile pieces. The gaps should allow geckos just enough space to fit the width of their bodies. Otherwise, the geckos will fail to take shelter, which is absolutely essential to their well-being. As we can see, there is no need to create a complicated design. I have tried to play off the different colors of geckos in order to achieve a suitable mineral mixture that recreates their environment.

|

|

December-January |

Febuary-April 15 |

April 15-Sept. 15

|

Sept. 15-Dec. 1 |

|

Mean daytime temperature (hottest point)

|

20-23°C [27°C] |

26-30°C [32-35°C] |

30-33°C [40-42°C] |

26-30°C [32-35°C] |

|

Night-time temperature

|

15-19°C |

20-22°C |

20-24°C |

20-22°C |

|

Frequency of misting*

|

none |

Heavy misting every other day |

Moderate, twice a week |

Heavy misting every other day |

Fig. 5 : temperature and humidity in captivity by season

* : performed using a handheld sprayer for indoor plants with water at 25 ° C.

|

|

December-January |

Febuary-April 15 |

April 15-Sept. 15

|

Sept. 15-Dec. 1 |

|

Duration of artificial lighting and daily heat*

|

10 hours |

10h =>12h |

14h |

12h=>10h |

|

luminosity and % of UVA and UVB at 20 cm from the lamp on the luminosity spectrum (measured via professional Zoomed® and luxmètre) |

≤ 300-400 lux

15,7 %UVA

3,9% UVB |

8000-10000 lux

18,9% UVA

4,4% UVB |

≥ 15000-18000 lux 21,3% UVA

4,6%UVB |

8000-10000 lux

19,3 % UVA

4,6%UVB |

* : Automatically set using an integrated electrical outlet timer (” timer “).

Fig.6 : illumination of the terrarium during its seasonal cycle

Important note: changes in temperature and illumination are not made “suddenly” but by gradually increasing or decreasing the values given in Fig. 5 and 6 over a period of two weeks.

Nutrition

These geckos should be fed in the evening, just before lights out . The food consists of subadult (1-1.5 cm / ½”) house crickets (Acheta domestica) and sometimes young locusts (Schistocerca gregaria and Locusta migratoria as available) of the same size (stages 2 and 3 in their development) , and juvenile cockroaches B. lateralis (“red runners”), or even “silverfish” (Lepisma sp.) which are very easy to breed.

The prey must be properly gutloaded at least 24 hours in advance with sources of protein (dry dog food in small quantities for the crickets and cockroaches, wheat bran for all, dry bread for cockroaches), greens (various salads except lettuce [toxic], including but not limited to collard greens, dandelion leaves and flowers in season, all plants with a phosphate ratio ≥ 2 as it should be for reptiles), peeled carrots (source of vitamin A) , peeled apples (pectin intake), peeled and diced zucchini, orange slices (vitamin C). It’s important to avoid food which is toxic for reptiles: potatoes and potato plant leaves, lettuce, tomatoes, on the basis of the concentration of toxins along the food chain. In this way, the feeders will contain a maximum of varied and complete nutrients. Insects are sprinkled at every meal with Miner -All I® (Sticky Tongue Farm® ) (without phosphorus with vitamin D3 to 4400 IU / kg and a variety of minerals) and once a month with Nekton Rep® produced and marketed in Germany. This is a multivitamin complex ideal for gekkonidae . I advise against the use of mealworms, superworms and B. dubia roaches or Gromphadorrhina portentosa, since these feeders are too chitinous and difficult to digest, and hive moths (Galleria mellonella), which are too fatty for these geckos who are already prone to obesity. I feed sparingly in winter with reduced weekly meals (3-4 prey items per gecko). During periods of temperature transitioning, the rate increases to twice a week with 6 prey items per gecko, and in the summer also twice a week but up to 10 prey items per gecko. It is essential to remove prey that has not been consumed from the terrarium the next day and not to transfer it to other terrariums in order to prevent possible cross-contamination. In summer, small moths attracted to light and lacewings are a tidbit that the geckos appreciate.

NEVER FEED PREY THAT IS TOO LARGE which would be likely to attack and injure the geckos, especially adult crickets. A. loveridgei’s skin is indeed easily targeted by the powerful mandibles of G. bimaculatus crickets or G. domestica adults. Do not hesitate to reduce the amount of food in cases of obviously overweight captive specimens. Indeed, in the wild they are dependent on hatching and breeding cycles of insects, so they “stuff themselves” for short periods with many prey items and can then spend several weeks without eating much; short periods of fasting, on the order of several weeks, are beneficial to the health of these geckos.

Fig. 7: Afroedura major wild caught male (we can make out the red mites which are visible on the hind leg at the tarsus). A related species to A. loveridgei. Photo © Jon Boone (http://www.jonboone.com) illustrating the extreme flattening of the body in a normal subject .

Health: Prevention

It is unlikely at this time to find specimens taken from the wild on the market. Jon Boone, the world-famous breeder, breeds this species regularly and offers specimens F2 to F4 (2-4 generations in captivity) in perfect health from several breeding groups, so a minimum of genetic mixing is assured. In case of doubt of origin, or when importation from Mozambique is proven , it is important to systematically perform first, a thorough body search for ecto-parasites, especially mites which are often lodged in the folds of skin or joints, and second, analysis of stool samples at several time intervals via a veterinary laboratory. Since most internal parasites follow their own specific life cycles, one negative sample is not evidence of absence of internal parasites. I don’t recommend any prophylactic treatment based on personal “judgment” where there is no evidence of parasitosis. These treatments are more or less toxic to such small lizards. Analysis of two samples of fresh stool, placed immediately into sterile jars, three weeks apart, constitutes a reliable protocol to ensure the absence of internal parasites, or, where applicable, their presence. Knowing the exact type of parasite allows you to apply a more targeted treatment under veterinary supervision. Outside of these preventative recommendations, A. loveridgei is a robust gecko that does not present any particular problem. My only mishap in more than three years of caring for these geckos in captivity was a case of bad shed on a female, quickly resolved with warm baths. It is for this reason that we should not neglect the misting described in Fig. 5.

Reproduction

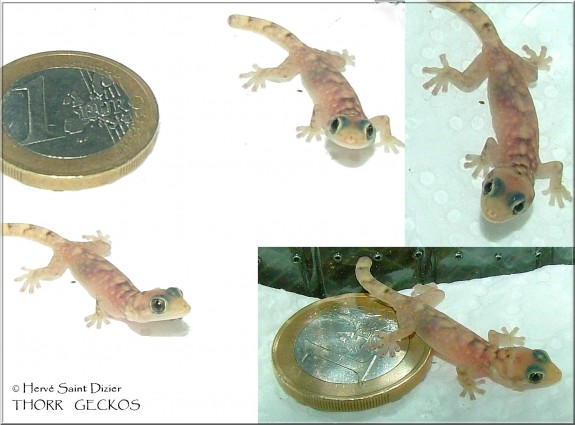

Fig. 8: Day old juvenile hatchlings

Captive breeding of this species is not easy, even if maintaining these geckos doesn’t pose any particular problems (Jon Boone, pers. Comm.). Two of us in Europe, Alessio Paoletti (Italy) and myself have been been successful, although we do not use the same cycles of temperature and humidity. Paoletti utilizes overall drier conditions and decreases the winter temperatures more than I do (pers. Comm.). I was the first of the two of us to produce juveniles of this species, with A. Paoletti following soon after. Winter cooling is not required for reproducing the species. In my first year of breeding, my trio reproduced without it. The eggs, two in number, are clearly visible through the abdomen of female. A. Paoletti and I have had a number of infertile clutches produced as well.

Clutches are laid every 4 to 5 weeks and two eggs are firmly glued to stones, so it is impossible to incubate them anywhere other than in the terrarium. I have noticed that females are particularly fond of using the corners of the terrarium as a nesting site, making any attempt to remove the eggs without breaking them even more difficult. The eggs measure ± 11mm at the largest dimension and are slightly oblong . I have observed production of up to four clutches a year, from late summer until early December, for three full years.

♦ I have protected the eggs with gauze (woven bandages for medical use) fearing that adults would eat the hatchlings. I found juveniles, with a total length between 26 and 29mm and proportionally shorter tails than those of the adults, with a blunt end (clearly visible in Fig.8) , within this protective envelope.

♦ the incubation temperature varied between 20°C and 34-35 where the eggs were glued, relatively close to the main heating source. It is therefore impossible to draw conclusions about a possible TSD (sex determined by the incubation temperature) or to set specific values for it.

♦ I Have carefully avoided spraying water near the eggs , so as not to risk drowning the embryos. By contrast when there are clutches in the terrarium, I misted more liberally while maintaining the misting protocol indicated in fig.5.

♦ If I happened to find clutches lying on the ground, it was due to them being poorly “glued” by the geckos or simply infertile. Fertile eggs have hatched from 76 to 96 days after being laid.

♦ I have incomplete information about the male/female ratio of juveniles: for the 6 specimens for which I collected data (more than a dozen hatched, and one died after a few days), 2 were male and 4 were female.

Hatchlings are first fed pinhead crickets (development stage 1 of these insects), or possibly Drosophila (flightless strains) .They are kept in groups of two or three in terrariums 15x15x20 cm (6 ”) set up similarly to those of the adults with the same temperature and humidity conditions, except that I do not make them undergo the cool and dry period in December-January, especially if they hatch close to these dates. They must be fed frequently, once every two days beginning 48 hours after their first shed following hatching. As they grow, the prey size and interval between meals is gradually increased. Misting is essential for their survival, on the same schedule as the adults.

Fig. 9 : A pair of hatchlings : the male is the one without the marked endolymphatic sacs.

Conclusion

Afroedura loveridgei remains a “confidential” species in both North America and Europe. Although they are simple to maintain, their reproduction, however, is not easy. This is one of the many unknown species among gekkonidae that deserves the attention of breeders who have experience with other species that glue their eggs on hard surfaces. It is also a gecko whose security in its natural environment can quickly become a concern, another reason to make the effort to work with this type of species. Their coloring makes them particularly attractive even if their overall morphology can be confusing. Discreet and shy, they are not able to call attention to their existence in a clear and noticeable manner in my experience . They are, nonetheless, affordable financially, most likely because of the limited knowledge currently available about them and the lack of potential buyers . However, this should not discourage anyone: it is the dissemination of as much information as possible about this species that attracts the interest of other gecko lovers.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jon Boone, Johan Marais, and Alessio Paoletti in particular for work both in the native environment of this species and in captivity, as well as Sophie Royer and Johanne Ouellette.

References:

‘Checklist’ de Répteis de Moçambique – Checklist of Reptiles of Mozambique

Alexander G. and Marais J. 2007, A guide to the reptiles of Southern Africa, Struik Publ., Cape Town, 410 pp.

Auerbach,R.D. 1987. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Botswana. Mokwepa Consultants, Botswana, 295 pp.

Bauer A M. Good D A. Branch W R. 1997. The taxonomy of the Southern African leaf-toed geckos (Squamata: Gekkonidae), with a review of Old World “Phyllodactylus” and the description of five new genera. Proc. Cal. Acad. Sci. 49 (14): 447-497.

Boelens, Watkins & Grayson, 2009 : The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 1-296

Branch, W. R. 1998. Field Guide to the Snakes and Other Reptiles of Southern Africa. Fully Revised and Updated to Include 83 New Species. Ralph Curtis Books (Sanibel Island, Florida), 399 S.

Broadley, D. G. 1963. Three new lizards from South Nyasaland and Tete. Ann. Mag. nat. Hist. (12) 6:285—288.

Broadley, D.G. 1964. A Note on the Domestication of Afroedura transvaalica Jour. Herp. Ass. Rhodesia (22): 16-17

Broadley,D.G. 1962. On some reptile collections from the North-Western and North-Eastern Districts of Southern Rhodesia 1958-1961, with descriptions of four new lizards. Occ. Pap. Nat. Mus. South. Rhodesia 26 (B): 787-843

FitzSimons, V. F. 1930. Descriptions of new South African Reptilia and Batrachia, with distribution records of allied species in the Transvaal Museum collection. Ann. Transvaal Mus. 14: 20-48.

Hewitt,J. 1925. On some new species of Reptiles and Amphibians from South Africa. Rec. Albany Mus. (Grahamstown) 3: 343-370

Rösler, Herbert 1995. Geckos der Welt – Alle Gattungen. Urania, Leipzig, 256 pp.

[N° taxonomique international d’Afroedura loveridgei/ Taxonomic number 818004]

One Comment

Leave a ReplyOne Ping

Pingback:Un gecko rupicole rare : le Gecko Plat de Loveridge, Afroedura loveridgei - Gecko Time - Gecko Time