One of my personal strengths is that I am very good at organization. One of my personal failings is that I am poor on following through with all the items I’ve organized. That can present a problem. Let me share with you how I got my breeding records and Gecko room organized for the 2012 breeding season. You might find some of these practices useful . . . or not!

[ad#sponsor]

Pre Season Preparations

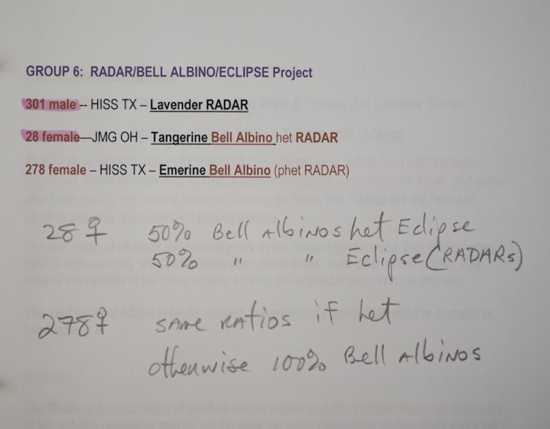

The 2012 season really began in the winter of 2011. That’s when I mulled over the genetics of the breeding size Geks I had in residence and considered exactly how I wanted to breed them. Some of the planned groups were easy to develop. For instance, I had several Tangerines from various sources to set up, but they largely fell into easy groupings, at first. Then I had to recheck possible genetic outcomes. I use one of the popular online “genetics calculators” to help me out. My best Hypo Tangerine male is from JMG and he is het Raptor. So a nice Sunglow, and an even nicer Hypo Tang from JMG, naturally fit well into the Hypo Tang male’s group. The Sunglow female could produce some Tremper Albinos with this male, and, in fact, the pair did produce one. Similar thinking went into each of the groups as I made my plans. Each group was established, then a few were re-arranged to leverage the genetic potential of the breeding animals. This resulted in a list with each male (all my Geks are assigned ID numbers), a group number, and the females for each group.

Setting up the Records and Labels

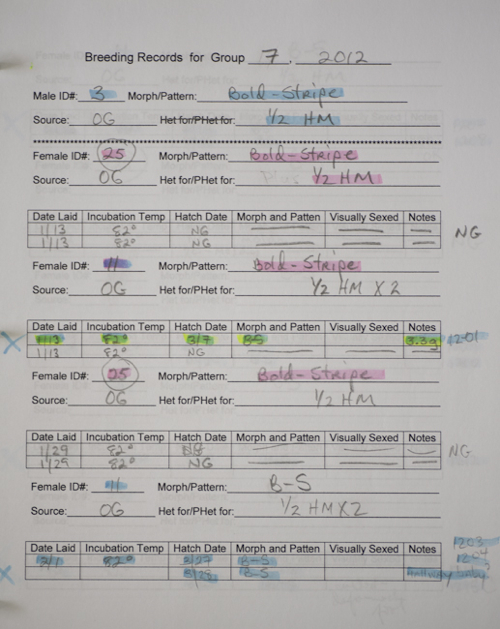

The list, in turn, produced a three-ring binder with an individual record sheet for each gecko, the gecko’s photo, source information, morph, and het, or possible het, information. There was a section in the binder for each group. In a separate, smaller three-ring binder I organized sheets to keep track of the females as they laid eggs — noting date laid, date hatched, morphs produced, and notes.

In the front of that binder were several sheets with large circles that each represented a deli-cup. The deli-cups with Geos had four quadrants, representing four sets of eggs from four females. On the circle I noted ID numbers of the parents (1 x 300, for example), date laid, date hatched, and other pertinent info (like condition of the eggs when placed in the cup-large, small, flaccid, turgid, etc). Others had no quadrants and represented a deli-cup with one set of eggs from one female. The same info was affixed on the record sheet and this mirrored the info on the deli-cup lid.

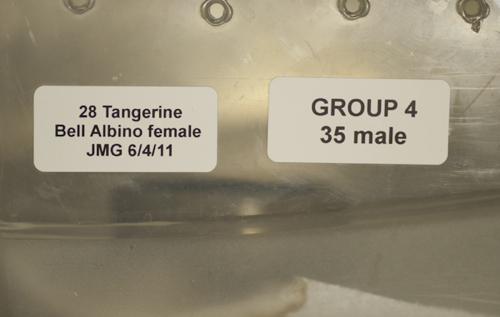

My breeder males were in a single rack by themselves in 16qt plastic tubs, and all females were housed in 32qt plastic trays in three other racks. After I identified the groups for each gecko, I printed a label with the group number in large letters and the male’s number that headed the breeding group . The Hypo Tangerine male was the Group 1 male; the Hypo Tang and Sunglow females were also group 1 breeders. I affixed labels with a large “Group 1” on each of their tubs. I needed to do this as I rotated the males through all the trays and this allowed me to find each female when there was more than one female assigned to that male. With 21 females in the racks this worked quite nicely. And the 12 males were rotated about every two weeks unless the male was mated with only one female, as a few were.

In these cases, the pair stayed together with no ‘time out” separations for the entire breeding season. There were no issues until a few weeks ago. But by then I was separating the breeding groups, selling the males and females I wouldn’t need for the 2013 season (largely based on breeding and fertility performance) to a local reptile store, and tidying up the gecko room. One male decided to take a bite out of one of the female’s tails–the only such instance the whole breeding season of a piece bitten out of a tail.

Breeding Rotations

When I placed a male into a female’s tray I affixed a label to the side of the tray. This label had a yellow sunburst in the middle and a black “M” was in the center of the sunburst.

Of course, the “M” stood for male and gave me a quick visual reference as to which female had been with a male. Every time the male was rotated through that female’s tray I added another sunburst label. This provided an easy to see visual reference for me to keep track of a male’s visits with the females in his breeding group. I find this easier than marking the information in a record book, although I have one of those as well. Additionally, each male had a white 3 x 5 card that followed him from tray to tray. His ID# and morph info were on the card, and any het or possible het he might carry or might be hiding was noted. When he was placed with a female, the date he arrived, or when he left and was moved to the next tray, was noted on the card. This card was placed next to the tray on the rack. I could look through the racks to see quickly where each male was in residence. I am quite visual, hence my use of visual cues.

When each female laid eggs, I placed a bright gold Avery round label on the side of her tray. This label had a large red “X” marked through the label (photo 6). I added the date the eggs were laid in one of the quadrants on the label. So each label provided four spots for me to make note of the date the eggs were laid. This allowed me a way to look at the trays to see which female was laying eggs–how many, how often, and on what date. It also turned out that this gave me an easy way to discern the success of regulating the temperature in my racks. For example, one day I noticed that only two of the three female racks had those bright gold, red “X”ed labels affixed and were producing eggs. Those bright gold labels allowed me to see this trend. In fact, how could I miss it? I adjusted the temps UP on the rack in question and the eggs started showing up a few weeks later. At age 60 something, a visual labeling approach saves wear and tear on the few brain cells I have left. Kept me from making too many mistakes of which I am aware. Ah, I guess I best share one before I close.

The One that Almost Got Away

At the start of the season, I had a hatchling emerge and waited for the second egg from that clutch to hatch. After three days I assumed it wouldn’t hatch and tossed the egg into the garbage can in the gecko room. A few days later my wife noticed a baby gecko walking down the hallway near the gecko room door and alerted me. At first I was dumbfounded. The first thing that popped into my mind was, “How did you get out of the neonate rack?” I checked the trays and they were all snugly secured in the rack. I pulled out the one tray in which I thought the baby gecko belonged and spied a gecko already in that tray. “What the . . . ?” Seems the little gal hatched in the garbage can, somehow climbed out, made its way under the gecko room door, and into the hallway. I’m glad I had good records to help me sort out that conundrum.