Anyone involved in the online leopard gecko community can recite the ideal leopard gecko setup: paper towel or tile, belly heat controlled with a thermostat, a dry hide, a humid hide, and a water dish. This simple setup works, and it has saved the lives of many leopard geckos previously kept in inadequate conditions due to ignorance. Still, many keepers wonder about creating more naturalistic enclosures.

Considering a Bioactive Setup

I fell in love with leopard geckos when I took in a rescue in terrible condition. At the time, I didn’t expect him to live, but he made an incredible recovery once provided with proper care. He spent over a year in a simple, modern setup before being moved into a larger display cage with more hides and climbing areas. I installed a small light fixture with a low-wattage UVB compact fluorescent bulb. A hardy haworthia succulent followed that. Even then, my gecko’s home didn’t seem adequate. I’ve spent a great deal of time wandering zoos and nature centers, transfixed by the elaborate habitats and their inhabitants. My leopard gecko’s enclosure, while it provided all his basic needs, looked barren in comparison.

I began researching the natural habitat of leopard geckos. My search for natural reptile habitats in captivity led me to the resurgent bioactive reptile community. Because naturalistic enclosures with substrate cannot be cleaned in the standard way, bioactive enclosures use a population of invertebrates and microbes to break down waste and keep the substrate clean. While tropical and forest setups are more common, some pioneering individuals have successfully designed enclosures for desert species such as bearded dragons and Uromastyx. I wondered, could I adapt those methods to my leopard gecko cage?

The majority of bioactive enclosures use lighting to provide basking heat. I wanted to utilize the existing floor heat and cooler lighting in my leopard gecko cage instead. One of the reasons I enjoy leopard geckos is the fact that they do not require large enclosures or heat lamps. I experimented with cycling the heat in my cage, warmer during the day and cooler at night, and noticed that my gecko seemed healthier and brighter overall when provided with constant, steady floor heat. This floor heat would not work through thick layers of bioactive substrate. I had the idea of building substrate around caves while leaving the insides bare, which would allow me to continue using belly heat and eliminate the need for a heat lamp.

The next question was how to make the enclosure bioactive. For desert setups, hardier insects are needed, such as lesser mealworms, mealworms, and superworms, and their beetles. Having humidity in the lower layers is also vital in order to maintain a population of good bacteria and fungi to break down waste. Other bioactive builders reported success with creating small humid refuges for custodians such as isopods. With that in mind, I decided to create a more humid substrate to use in a limited area while keeping the majority of the surface a hard-packed clay mix that would match native leopard gecko habitat.

The concept solidified over the following months. I purchased various substrates and experimented with small batches until I found mixes that behaved as I wanted. Finally, I was ready to build my desert.

Construction

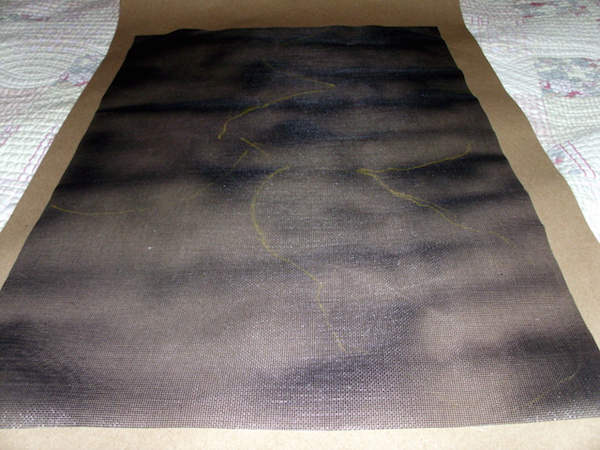

I cut out a piece of brown paper and drainage mesh to fit the floor of the cage. Then, I arranged the hides and cage furniture on the mesh and traced them with chalk. This allowed me to cut a piece of drainage mesh for the humid portion of the cage without overlapping the hides. With most of the hides placed in the cage, I put a thin layer (approx. 1 inch) of light-weight drainage medium on the humid side and covered it with drainage mesh. This small area would allow excess water to drain from the substrate and prevent it from becoming saturated.

The next layer was designed to hold enough humidity to support the bioactive custodians. The humid mix was 2 parts sand, 3 parts fine coco fiber (Zoo Med Eco Earth), and 3 parts organic potting soil. To jumpstart bioactivity, I seeded the humid mix with ¼ teaspoon Bene-Bac (bird/reptile powder) and 2 teaspoons organic compost starter. I mixed the substrate well with water to make it damp and then packed it loosely around a potted haworthia plant and the gecko’s humid hide. I chose to keep the plant potted so I could provide a different potting mixture and protect its roots from digging.

The final layer was the clay substrate, designed to be shaped when wet and dry to a hard crust. This mix was 4 parts Zoo Med Excavator clay, 3 parts sand, 1 part Exo Terra Riverbed sand (finer grain), and 2 parts organic potting soil, which I made wet enough to clump. The clay substrate was packed tightly around the furniture and sculpted into a desert landscape. Because I wanted to be able to remove the humid hide, I left some wiggle room around it. A small area up front was not covered with clay. This was to be the humid refuge for the custodians. The final touches were small cork bark flats, a feeding station, and a magnetic wall cave to add some climbing opportunity.

The cage was left open for a week, and I occasionally ran a fan into it to accelerate the drying process. When the surface had hardened and relative humidity remained below 60% with the door closed, it was time to add the insects. I chose to use mealworms and beetles (Tenebrio molitor), superworm beetles (Zophobas morio), pill bug isopods (Armadillidium vulgare), and tropical springtails. I also did a bit of local collecting, which provided me with worms, millipedes, and native isopods. I added them to the humid area and covered with oak leaf litter before replacing the cork bark pieces.

The bioactive enclosure was allowed to cycle for almost a month. During that time, I monitored the temperature and humidity closely. I misted the humid areas every other day and watered the plant and humid refuge every other week. I also added a bit of vegetable and sprinkled some insect chow in the corners every other day, which helped encourage the custodians to forage. The insect population did very well, and I even spotted new young as they began breeding.

By the time a month passed, the relative humidity was 45% – 55% during the day, and the floor temperature inside the warm hide was 88 – 90 ℉. The air temperature above ground was 75 – 79 ℉ during the day. The small light fixture heats the air on the warm end of the cage during the day, and that temperature range is typical for my display enclosures in summer. The relative humidity was slightly higher in the bioactive cage, but this range is fine for a leopard gecko. In fact, “The Eyelash Geckos” goes so far as to recommend that humidity never drop below 50% for the species. Unlike some of their better-adapted cousins, leopard geckos have thin skin that makes them prone to dehydration. They do not benefit from exceedingly dry conditions.

While the enclosure was cycling, I had my leopard gecko tested for fecal parasites by our veterinarian and monitored him to ensure he was in good health. I did not want to introduce dangerous parasites or bacteria into the enclosure. When I was satisfied that the environmental conditions in the cage were stable and my gecko was ready, I introduce him to his new home. The first few days, he was very restless and nervous. This was to be expected, as I had essentially taken him out of his home territory. After the first week, he had settled in and begun eating regularly. It has been over a month since, and he is back to his normal behavior, eating well and moving around the enclosure confidently. He also continues his habit of occasional morning basking, which tells me all I need about the practice of providing UVB lighting to leopard geckos.

Maintenance

Maintaining a bioactive enclosure is no more difficult than keeping a simpler cage. The custodians devour feces and food scraps, while the hard, white urates remain untouched. I bury some urates into the humid area to encourage the growth of bacteria that will break down waste, and I remove the rest.

I still add bits of vegetable and insect chow a few times a week to keep the population of custodians going strong. New leaf litter also needs to be added every so often, as it is eaten. Make sure you do not feed so much that leftover food begins to build up–only feed what your custodians will devour in a day or so. If your population gets out of control, you can cut back on the food provided.

The humid areas are misted every other day and watered every week or so to keep them damp, not soaked, and the haworthia is watered well every two weeks. I expect to cut back on watering during the winter, when the lower temperatures will cause moisture to evaporate more slowly.

Conclusion

This project has been very rewarding, and I plan to repeat the transition with other geckos in the future. Part of my goal in writing this article is to show other leopard gecko keepers that a natural, living desert vivarium is within reach. There is a lot of backlash against any particulate substrate in keeping leopard geckos, based on extreme cases of neglect and poor husbandry, but these creatures are designed for desert living. They are more than capable of thriving in an environment with loose substrate.

I feel one key point in all this is to create a bioactive ecosystem. A substrate, by itself, is bound to build up waste and become unhealthy over time, but creating an environment in which waste is degraded naturally and the substrate is shifted and maintained by natural means opens the possibility of moving beyond a bare landscape. Once a bioactive enclosure is running, dedicated monitoring and maintenance can ensure it thrives for many years.

Another vital point is to make sure you achieve the right environment for your species. This means carefully monitoring temperature and humidity with precise tools (ditch those dials!). Make sure you have a hiding area that reaches the appropriate temperature for digestion and good health. There needs to be humid refuges where your gecko can stay hydrated and shed easily. Overall, your enclosure should be large enough to provide a gradient of both temperature and humidity so your gecko can move to where it is comfortable.

A final point: know yourself and your gecko. These types of enclosures are not for everyone, and some keepers are much more comfortable with modern, clean setups. Geckos who are ill or have special needs may benefit from simpler enclosures. The important thing is providing an environment that keeps your gecko in good health and spirits, whatever way you choose to do so. If you feel yourself being pulled into the grand setup debate, repeat after me: there isn’t one right way to keep a leopard gecko.

Resources

- ● GeckoForums – Bioactive Leopard Gecko Experiments

http://geckoforums.net/f175-vivariums/102660.htm

A chronicle of the project as it unfolded, where I will continue to post updates. - ● Facebook – Reptile and Amphibian Bioactive Setups

https://www.facebook.com/groups/bioactiveherps/

This group is devoted to promoting the use of bioactive vivariums and served as a source of inspiration for my leopard gecko project. - ● The Eyelash Geckos: Care, Breeding and Natural History

Hermann Seufer, Yuri Kaverkin, and Andreas Kirschner. Karlsruhe, Germany: Kirschner & Seufer Verlag, 2005.

This guide covers many Eublepharid geckos. The small section on leopard geckos alone makes this book worth owning for those interested in their natural habitats and behaviors.

Hi! Why are there no more new posts since August?((

Good question! Gecko Time depends on people who are willing to write articles (not to mention willing to respond when I email them to find out where their promised article is). In November 2014 we ran an article called “What’s going on with Gecko Time?” where I explained that after 5 1/2 years of publishing weekly, we were no longer able to sustain that amount of output and that Gecko Time would publish when it had something available. I’m happy to say that there will be a new Gecko Time article running tomorrow (10/6) as well as another article running the following week 10/13. I have several articles “in the can” that the author has not yet approved for me to run and at least one promised article that has not showed up yet. I encourage anyone interested in writing to Gecko Time to contact me and let me know what they’d like to write about.

Hi ! Thank you for your insightful article. There are things that i want to ask. First, where can i find both drainage mesh and the medium? Can you mention one type of brand or substitutions for those items? Readers/hobbyists from outside your country find out to be difficult to find the items needed to build such an enclosure. Secondly.. I may ask you later ! Thanks

I don’t think the original author will see this question so I will respond. It’s hard for me to know what brands and availability you have if you’re in a country outside the US, so I’ll try to be general. In the US there are hydroponics stores that sell “expanded clay balls”, so you should check the equivalent in your country. Also, we have home improvement stores that sell a roll of vinyl mesh that people would buy to repair their screen windows and doors. That’s what I use for my bioactive set-ups. I use coco-fiber for the substrate. If you can’t find that, you should probably look for a Facebook group about bioactive setups in your part of the world and see what people use.

Hi, Tobi,

I agree with Aliza on the window screening. That’s usually common enough to find; try to find a brand that is not metal, as aluminum will rust over time. If you can’t find that, I know people have used weed-blocking sheets or fabrics as well. Fabrics will rot away eventually if exposed to constant moisture though.

For the drainage medium, clay balls / LECA is also a good recommendation. You can certainly use other things… Rocks/gravel is an option (very heavy but will work), and a lot of folks even use branches, especially in desert setups where they will not be a large amount of water in the base to rot them away.

And I do get email notices when comments are made, so I’ll try to stop by and answer any questions that may come up.

I realise this is a litle late to the game, but I’ve only just come across this page.

Wonderful article, it’s really great to see people getting interested in Bioactive Setups and trying them out for themselves. the difference in behaviour when allowed access to natural environments is astounding.

To Tobi, if you are UK based, or even EU based, plase checkout Bioactive Herps. We aim to have everything in stock for keepers to create anything from basic, to more ambitious, bioactive setups.

Gecko Time – If ever you would like a short article or write up regarding Bioactive Setups in general or more specifc, please feel free to send me an email. I’d be happy to write one up especially for you, and have plenty of time to get them done and to you without much delay.

Thanks

If you can think of an article relating to geckos and bioactive setups that is different enough from the 2 we’ve already published, send me an email with your proposal. Always glad to publish something new and useful.

I will have a look through your current articles and see if I can come up with some good content 🙂 I’m always happy to get more information out there.

Thank you

Thank you for your explanation. I received a notification about it to my e-mail only today for some reason..but I am happy to see new articles. If you could write an article about morphs (in general, for beginners) it will be great.

I disagree with bringing in outside bugs because for the same reason you don’t feed your gecko wild bugs as they will have a chance to bring in parasites

There’s always that question of how clean is too clean and how “natural” is too natural. Different people have different decision points. I and a number of other people have not had a problem with this practice, though there are other people who recommend breeding any creatures from outside for several generations before introducing them.

You can certainly purchase all your custodians as opposed to collecting outside. 🙂

The unfortunate truth is that any insects can harbor parasites, whether they are wild or captive bred. There are plenty of reptiles that have only ever been exposed to store-bought insects that still end up infected with parasites. That is why periodic testing and monitoring your reptiles is important, whether you use bioactive or sterile setups.

Hi, I’ve tried to find answers elsewhere but to no avail. Just wondering if you could help regarding the springtails and their requirements, I have a moist hide with damp eco earth in and I know they would thrive in there; but I’m wondering: If the rest of the setup is very dry, would they suffer because of that? I’m looking into making a fairly simple bioactive setup, eliminating the woodlice/worms as they need the moisture and replacing them with dermestid beetles and larvae. However I have no knowledge of springtails (or even the difference between tropical and temperate) and how they would react to a low humidity environment. I would like to keep the setup as close to a ‘clean’ one in order avoid, if possible, having to add drainage layers.

Hopefully you’ll get a response from the author as well. The dermestid beetles may be more viable for this environment, but I would guess the springtails would hang out in the humid hide and under the water dish.

Springtails definitely need humidity, so the more humid areas you can provide, the larger your population will be. They cannot survive in the drier areas.

None of my leopard gecko enclosures have a large springtail population because the humid areas are small. Every so often, I’ll see a little population spike during the humid summer months, but for the most part, they’ve disappeared.

I have noticed another tiny insect species – psocids, also known as book lice. It’s likely these colonized from the leaf litter or from my own home, and they seem much more tolerant of the dry setup. I often see them out on the hot rocks during the day running around. They eat mold, so it’s a good thing to have them around in a bioactive setup.

There’s nowhere you can buy book lice that I know of though, so your best bet is to try to seed some with collected leaf litter.

My experience has evolved since writing this. They best custodians in my setups seem to be the pill bugs (Armadillidium vulgare) and the superworms and their beetles (Zophobas morio). I have not tried dermestids, mostly because they are known to fly in high temperatures, but if you use them, feel free to post here and let us know how they work out for you!

Dermestids have worked well for me and I rarely see them flying. They can overpopulate though and then the water dish is full of worms!

I just wanted to note that there are two newer articles on leopard geckos bioactive with some tweaks to this original setup.

Part 1: http://geckotime.com/holistic-design-in-bioactive-vivariums-leopard-geckos-part-1/

Part 2: http://geckotime.com/holistic-design-in-bioactive-vivariums%EF%BB%BF-leopard-geckos-part-2/

Thanks for pointing that out, Rachel.